Make your organization intelligent

As a leading consultant in Business Intelligence, we offer a small but high-quality range of Business Intelligence services. Our Business Intelligence guide focuses on what you want to achieve in the near future, what the business benefits are, and how to get there, in 5 steps. Becoming an intelligent organization means leveraging data to drive decision-making, optimizing processes, and fostering innovation. This guide is designed to help you identify key objectives, understand the potential gains, and implement a strategic approach to transform your organization. By following these five steps, you can effectively harness the power of BI, enhance operational efficiency, and gain a competitive edge in your industry.

Where are you now?

The current Business Intelligence situation will be addressed, discussed, analyzed, and compared with the best practices and newest available technologies. We will help you to quickly find out where improvements can be made.

Where do you want to go?

Based on the previous step and the expected business benefits, it’s smart to create a Business Intelligence plan, leading to a clear goal. What competitive advantage can be achieved by upgrading your current Business Intelligence system? What are the benefits for the business users and the IT professionals? How do you present the plan to your stakeholders and directors?

How do you get there?

Now that you know where you want to go, it’s time to formulate a Business Intelligence strategy for the future. This can be implemented by setting standards, implementing a Business Intelligence competency center, using Business Intelligence in the cloud, implementing a Business Intelligence framework, using one platform for Business Intelligence, or a combination of all of these options. Below you’ll find three in-depth topics so you can get more familiar with the key aspects of a good Business Intelligence strategy.

1. Business Intelligence strategy and governance

We can initiate and implement all sorts of projects in the field of Business Intelligence; we can have a magnificent system with an intelligent architecture; we can apply data mining ingeniously, but if we do not apply a lasting Business Intelligence strategy and governance, all of these efforts are useless, because they will not produce lasting results (or returns). What may happen, for example, is that the applications we have developed will not be used in the long term, simply because the relevance of the information is not being monitored periodically or because our attention to keeping our Business Intelligence systems up to date lessens. Of course, BI projects are important, but Business Intelligence is more than performing successful projects. It also involves selecting the right Business Intelligence tools and devising well-thought-out architectures.

We must realize that the Intelligent organization does not just happen; it may take years before we reach the highest possible level and this requires ongoing commitment from management, as well as a lot of attention to elementary practical and strategic aspects of Business Intelligence. In order to achieve an Intelligent organization we must not only draft a good Business Intelligence strategy and establish good BI governance, we must also – and more importantly – maintain both. Business Intelligence must become a habit, and alignment between registering processes, processing and responding, internal and external information, and business and technology must be central to this. In this chapter, we outline the course that organizations can pursue towards maximal intelligence, and we describe the main conditions and milestones. On our journey towards our ultimate destination – the Intelligent organization – we need to carry two essential tools with us:

- A BI roadmap: we need a map in order to determine the Business Intelligence strategy – the path to the ultimate goal – of the Intelligent organization. This concerns the continuous shifting of boundaries, recognizing obstacles in the landscape, and constantly increasing the level of ambition of Business Intelligence.

- A compass: this tool indicates our direction, ensures a balanced focus on the three basic processes of the Business Intelligence cycle, and forces the organization to combine internal en external information. A compass offers us guidance because it always points North – the summit of intelligence – even if we change direction. With our compass, we can always set course towards the top. This is all about Business Intelligence governance: giving direction to the intelligent organization.

An enthusiastic traveler requires both tools in order to find their way through the maze of technologies, BI tools, processes, disciplines, and visions that we encounter with Business Intelligence. The map and compass enable us to make better choices when it comes to desired projects and their priorities, which leads – among other things – to a higher return on these projects. Later we will discuss the BI competence center: the department that uses both a map and a compass in order to shape the Intelligent organization at a strategic level. The BI competence center also both governs and implements the necessary Business Intelligence activities and processes at an operational level.

2. The Business Intelligence roadmap

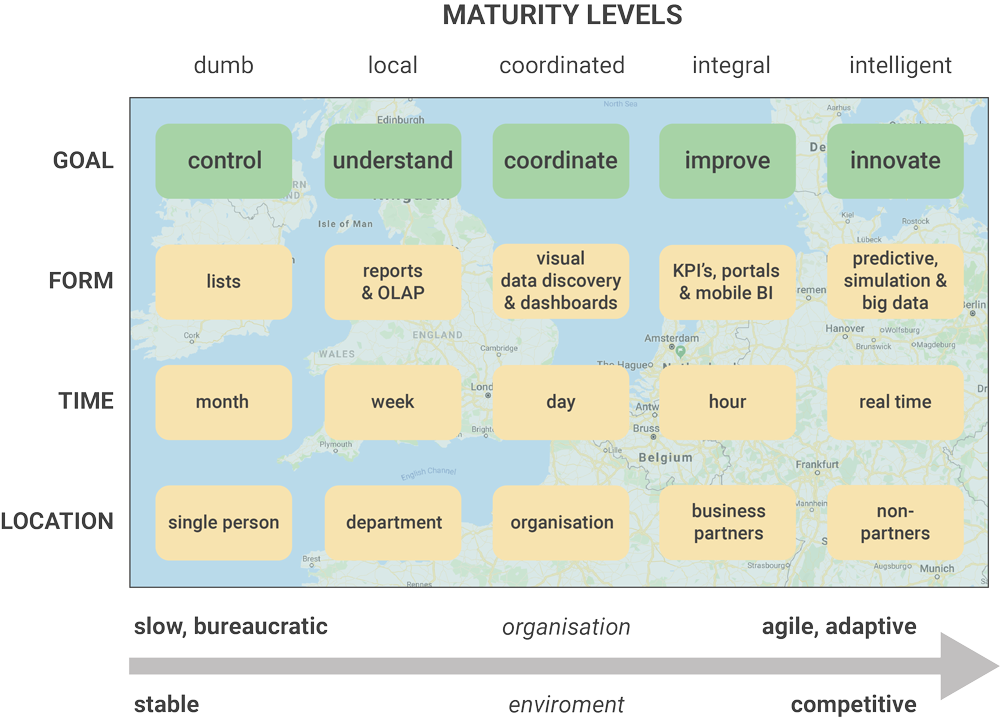

The different strategies and ambitions of the Intelligent organization can best be described by plotting the levels of ambitions against the four most essential dimensions of the concept of information:  Figure 1: the BI roadmap, including the BI strategies and levels of ambition.

Figure 1: the BI roadmap, including the BI strategies and levels of ambition.

- content: the purpose of the information (ambition level);

- form: the form in which the information is presented;

- time: the topicality of the information;

- location: the location – inside or outside the organization – where the information is used.

Usually, the dimensions are coordinated: when we create beautiful visualizations we don’t do this for one individual in the organization and when we don’t fully understand certain information, it’s unlikely that we will share the information with business partners.

The different strategies (or levels of ambition) generally exhibit a causal relationship with both the environment and the type of organization. We often come across the lowest level of ambition in sluggish, bureaucratic organizations with a product-oriented structure and a formal culture, which operate in a calm and stable environment. The highest level of ambition is usually applicable to very agile and adaptive organizations with market-oriented structures and informal, though performance-driven cultures, which operate in a highly competitive environment.

We can use the BI roadmap to measure where we stand as an organization, and subsequently to map out a long-term strategy in order to reach a higher level of ambition. Both the necessity and the will to achieve this higher level depend on several factors: the level of competition, the organizational culture, the maturity of the technology, and so forth. However, in all cases, we will need a business case that justifies investing in a higher ambition level. Reaching a higher level of ambition is not to suggest that we no longer use (or stop using) elements from the lower levels. If, for example, we decide to update reports on a daily basis, we may still need to report some management information on a monthly basis. The point here is that achieving a higher level of ambition offers us the opportunity to apply various refinements, both organizationally and technically.

Reaching a higher level of ambition paves the way for organizations to start organizing and operating differently. Business Intelligence can then be seen as an ‘enabler’ for a different organizational structure, a different management style, a different way of communicating with clients, how we value our employees, and so on. Of course, Business Intelligence is not the only ‘enabler’. We may (partially) achieve the same with ‘enablers’ such as knowledge management or internet technology. So as previously stated: Business Intelligence will increasingly work in harmony with other disciplines once we reach the higher levels of ambition.

The different organizational characteristics of each level of ambition should therefore not exclusively be associated with Business Intelligence, but as possible scenarios made possible through Business Intelligence. The BI roadmap can be seen as a well-marked route with clear ‘signposts’ that lead to permanent intelligent operations. This map is particularly useful for organizations that are yet to start with Business Intelligence or organizations that experience trouble with it.

3. Business Intelligence governance: the compass

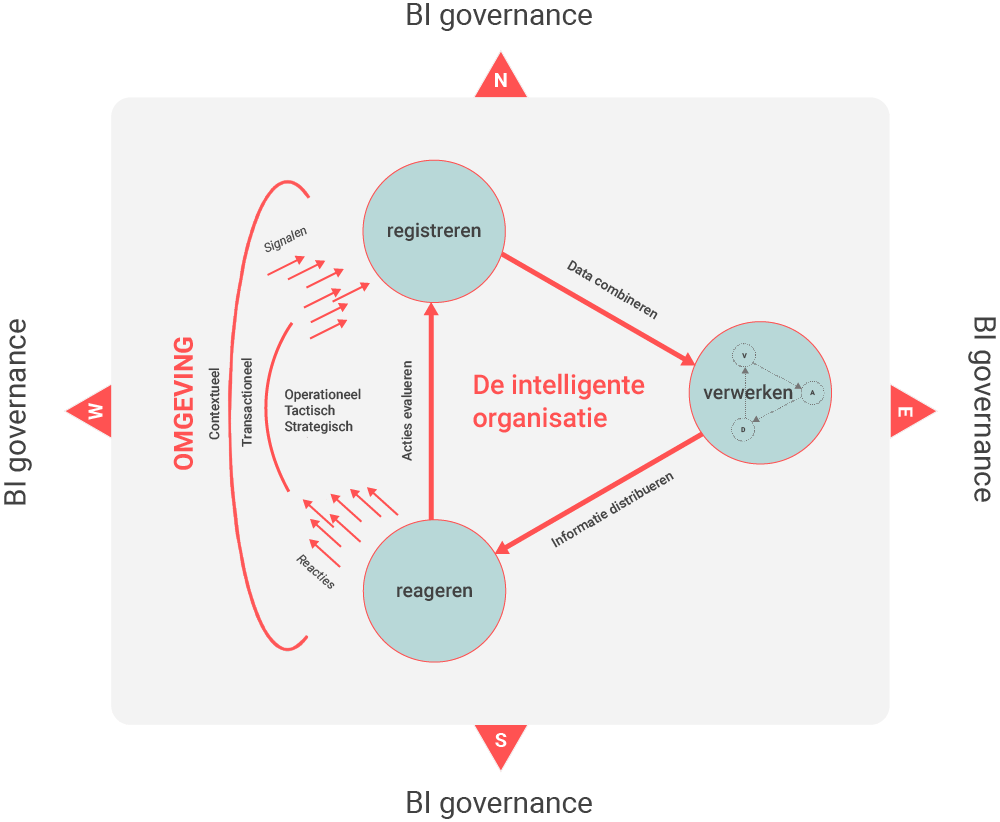

This section discusses the basic principles of Business Intelligence governance: the Intelligent organization evenly divides its attention between the three basic processes of the Business Intelligence cycle and aims for a good balance between contextual (external) and transactional (internal) information. This is shown in the figure below.

Figure 2: BI governance ensures that all the processes and facets of Business Intelligence are addressed and get the attention they deserve.

Figure 2: BI governance ensures that all the processes and facets of Business Intelligence are addressed and get the attention they deserve.

Although, from a traditional Business Intelligence point of view, the processing part (of the Business Intelligence cycle) is the most important and technically the most complex process, we must not forget that Business Intelligence (BI) also increases which signals an organization should register and how we should respond to these signals. In other words: the other processes are also important.

The point here is that we must create a closed-loop process for both the major and the minor Business Intelligence cycle. Thus, not only the three processes of the major Business Intelligence cycles – registering, processing, and responding – are attuned to one another but the minor Business Intelligence cycle is also characterized by its closed-loop nature. Based on the gathered data, the Intelligent organization will gain (new) insights with different kinds of BI reporting tools, which will lead to a requirement for additional data to be collected, preferably without having to adjust the existing registration systems.

We often see that during the pioneering phase of Business Intelligence, organizations only go through the minor Business Intelligence cycle: it is only at a later stage, once a higher level of ambition has been achieved, that these organizations seriously engage with the major Business Intelligence cycle. In any case, it is crucial (in this context) that there is a function – typically, the BI competence center – within the organization that monitors the relevance of the information and, if necessary, initiates projects and implements actions, either by collecting existing data or by registering new data. Moreover, BI governance will ensure that only the data relevant to decision-making are being registered – for example by taking account of this aspect when purchasing (or developing) the system. Additionally, BI governance aims to realize the best possible return on either the registered data or the access to this data, irrespective of whether it is recorded inside or outside the organization, obtainable with or without payment.

As the organization climbs the ladder of BI ambition, the phenomenon of BI Governance becomes increasingly important. If we ‘just’ wish to understand the organization (the lowest level of ambition), then we do not necessarily need to change anything or react differently. In addition, we need little or no external information. After all, we ‘only’ use Business Intelligence to gain better insight into our ‘own’ business operations. However, if we wish to innovate with Business Intelligence (the highest level of ambition), then it is extremely important that innovation management, strategic management, Business Intelligence, and change management are closely intertwined. External information about our competitors or about technological developments, for example, is important in order to be able to innovate.

4. Registration

Whilst defining the information needs, and often during the processing of the information, organizations may discover that they are not registering the signals – and do not have the data – they require to actually measure the performance or to get the insights they need to improve performance. If this is the case, the organization will have to go back to the first process of the major Business Intelligence cycle and try to work out what data is required. Subsequently – if possible – the organization will either adjust or extend the registration systems.

Case: Pension Fund

In 2003, a pension fund with managed assets of 53 billion started with Business Intelligence. Up until then, the fund used different systems from several external suppliers for the administration of the different types of assets – shares, bonds, futures, options, and mortgages. Once the information needs were successfully mapped, the organization optimistically began to draw up a functional design that would ideally contain a description of the sources and precise definitions of the required information.

Soon the pension fund realized this was not easy: the source systems were in fact very difficult to access, and comprehend, which made it impossible to determine an exact definition of the required information. The supplier was not willing to offer assistance because they felt the data model of the source system was a trade secret. The pension fund then tried to determine the data model on the basis of trial and error, which took several months. However, in order to be able to calculate the desired information, the fund also required data they had not yet registered. They, once again, turned to the supplier to ask if this data could be added to the application.

The supplier, however, was not willing to do this. Consequently, the organization developed a separate Business Intelligence ‘data management’ application in which the additional data could be entered. However, they soon realized that this data was also important for other applications and processes (besides BI) and therefore it was decided to transform the ‘management’ application into an additional registration system. In conclusion: as a result of the above-mentioned experiences and findings, the pension fund now selects both its suppliers and applications much more carefully and all their contracts (with suppliers) now contain a clause that states that the data model must be made available if requested.

Source Data Quality in Performance Measurement

The case above demonstrates that the completeness, quality, and meaning of source data are crucial when it comes to measuring performance properly. Organizations will need to go back to the registration process regularly in order to improve the registration of data, to sharpen the significance (and meaning) of data, or even to develop an entirely new registration system – in case of external strategic or tactical information. However, this should not prevent organizations from starting with Business Intelligence, because most gaps are in fact revealed faster when we apply Business Intelligence.

5. Responding

The information and knowledge that we gain with Business Intelligence may give rise to the elimination of certain products – that are, for example, no longer profitable– from the assortment, to enter new markets or to open up additional communication channels. Naturally, such actions will affect the first process of the Business Intelligence cycle: registering signals. When we open up new communication channels or when we enter new markets, we will need to adjust the operational systems with respect to their content (adding the new product in accordance with the existing structure), or their structure (entering a new market, for example, often requires adjusting the structure of tables in operational information system and sometimes even a completely new information system). This, once again, shows that effective Business Intelligence requires a cycle consisting of three basic processes that are closely intertwined. The Intelligent organization does not just use Business Intelligence to focus on the fast and accurate processing of signals into information and knowledge, but also ‘manages’ and influences the registration and response processes within the organization.

What can we offer you?

- 100% vendor-independent advice and process facilitation;

- investigation of the current situation;

- interviews with your business users & IT professionals;

- help with the BI software selection process;

- help you to present the plans and strategy to your directors;

- a second opinion.

Interested in our BI-strategy services?

Contact us and discover how we can help to develop and implement a future-proof Business Intelligence strategy.